In Radical Candor, Kim Scott outlines the different types of feedback that managers give, and the traps you can fall into when doing so. She has developed a system for giving effective feedback outlined below.

The TLDR is:

- Ideally, first build a relationship with anyone before giving them feedback. Make sure they know you care personally about them and their career.

- Then be extremely candid and clear with your critical feedback. Leave no room for interpretation.

- Do not sugarcoat feedback to make people feel better.

- Do not get personal or make sweeping statements. Be specific.

- Be humble. If you are wrong, you want to know.

- For positive feedback, be just as specific. Otherwise you’re just being insincere.

The following are excerpts taken from Kim's book, Radical Candor.

The four quadrants

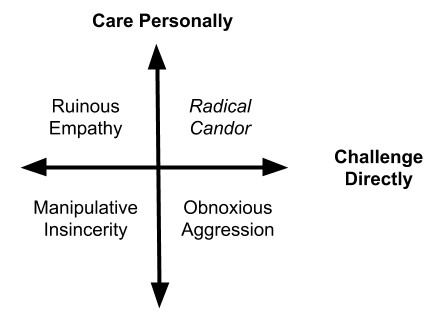

The four quadrants of feedback are Ruinous Empathy (the most common mistake), Manipulative Insincerity, Obnoxious Aggression, and Radical Candor.

Manipulative Insincerity

"People give praise and criticism that is manipulatively insincere when they are too focused on being liked or think they can gain some sort of political advantage by being fake—or when they are just too tired to care or argue any more.When you are overly worried about how people will perceive you, you’re less willing to say what needs to be said." - Kim Scott, Radical Candor

Feedback that is manipulatively insincere rarely reflects what the speaker actually thinks; rather, it’s an attempt to push the other person’s emotional buttons in return for some personal gain. Manipulatively insincere feedback happens when you don’t care enough about a person to challenge directly.

Obnoxious Aggression

When you criticize someone without taking time to show you care about them personally, your feedback feels obnoxiously aggressive to the recipient.

When managers belittle employees, embarrass them publicly, or freeze them out, their behavior falls into this quadrant.

"Obnoxious Aggression sometimes gets great results short-term but leaves a trail of dead bodies in its wake in the long run." - Kim Scott, Radical Candor

Often Obnoxious Aggression stems from fear. Fear of rejection. Fear of anyone questioning your authority. If you find yourself shutting people down, look inside and figure out what fear is driving that response.

An example of obnoxious aggression would be:

“You didn’t prepare an update for our one-on-one, Alex; quite frankly, I think you’re incompetent!”

Ruinous Empathy

Ruinous empathy is the most common mistake people make when giving feedback. Managers sugarcoat feedback in an attempt to make it land better, but in reality they dilute the message and undermine the feedback. What’s worse is that sometimes managers use ruinous empathy to justify not giving feedback at all!

"There’s a Russian anecdote about a guy who has to amputate his dog’s tail but loves him so much that he cuts it off an inch each day, rather than all at once. His desire to spare the dog pain and suffering only leads to more pain and suffering. Don’t allow yourself to become that kind of manager!"

-Kim Scott, Radical Candor

We sometimes hear people say, “I didn’t say exactly that, but they definitely knew what I meant.” Well, no one can read your mind. It’s much easier to say exactly what you mean to say and remove all room for interpretation.

"Managers rarely intend to ruin an employee’s chance of success or to handicap the entire team by letting poor performance slide. And yet, that is often the net result of Ruinous Empathy. Similarly, praise that’s ruinously empathetic is not effective because its primary goal is to make the person feel better rather than to point out really great work and push for more of it.

Ruinous Empathy can also prevent a manager from asking for criticism. Typically, when a manager asks an employee for criticism, the employee feels awkward at best, afraid at worst. Instead of pushing through the discomfort to get an employee to challenge them, managers who are being ruinously empathetic may be so eager to ease the awkwardness that they simply let the matter drop.

Managers often make the mistake of thinking that if they hang out in the Ruinous Empathy quadrant, they can build a relationship with their direct reports and then move over to Radical Candor. They’re pleasant to work with, but as time goes by, their employees start to realize that the only feedback they’ve received is “good job” and other vaguely positive comments. They know they’ve done some things wrong, but they’re not sure what, exactly. Their direct reports never know where they stand, and they aren’t being given an opportunity to learn or grow; they often stall or get fired. Not such a great way to build a relationship.”

— Kim Scott, Radical Candor

An example of ruinous empathy might be:

"When we put typos in emails to customers, it doesn’t look quite as professional as we should. I know you’re super busy, I totally get why this happens, but I’m hoping we can all make more of an effort."

Radical Candor

“Radical Candor” is what happens when you put “Care Personally” and “Challenge Directly” together.

People will believe that you care personally when they trust you and believe you have their best interests at heart. This will only happen if you forge a deep personal connection with them. Take the time to really get to know everyone on your team, their strengths, their weaknesses, their desires out of life. Realize we are all human beings, with human feelings, and even at work, we need to be seen as such.

Then communicate feedback clearly and candidly. Do not beat around the bush or sugarcoat feedback. You will only water down the message, serving no one. You need to give feedback that, in a way, does not call into question your confidence in their abilities but leaves no room for interpretation.

“Candid feedback is offered humbly. Implicit with candor is that you’re simply offering your view of what’s going on and that you expect people to offer theirs. If it turns out that in fact you’re the one who got it wrong, you want to know. You are giving the other person insight into your internal story about them and offering them a chance to change it.

It turns out that when people trust you and believe you care about them, they are much more likely to:

- Accept and act on your praise and criticism

- Tell you what they really think about what you are doing well and, more importantly, not doing so well

- Engage in this same behavior with one another

- Embrace their role on the team

- Focus on getting results

The most surprising thing about Radical Candor may be that its results are often the opposite of what you fear. You fear people will become angry or vindictive; instead they are usually grateful for the chance to talk it through. And even when you do get that initial anger, resentment, or sullenness, those emotions prove to be fleeting when the person knows you really care.”

- Kim Scott, Radical Candor

An example of radical candor might be:

“The widget feature is now 30 days delayed after the mutually agreed-upon deadline. This makes me feel fear because the story in my head is that you don’t appreciate deadlines. The rest of the marketing and sales team are geared around this deadline, and missing it causes a lot of disruption. Further still, if we don’t have a culture of keeping to our commitments, I fear that ultimately we will be slow to ship products, fail to raise a round, the company will go bankrupt, and everyone will lose their jobs. In the future, can you keep your commitments and deadlines?”

What happens in cases where you don’t have a personal connection with someone but still have candid feedback to give them? Give it to them anyway, with the same candor. It may upset them in the short term, but in the long term you will build that relationship and they will understand you are giving them feedback to try and help them.

An example of asking to give feedback to someone who you don't yet have a relationship with:

"You are extremely valuable to Clearbit (other group), and even though we don’t know each other very well yet, I wanted to give you some feedback. Are you open to that?"

Feedback rewrites

Providing ineffective feedback is one of the most common mistakes we see managers make. Time and time again, we see managers operating with ruinous empathy rather than being radically candid.

This is why we spend so much time during our manager training focused on good feedback. It’s also why we regularly audit the feedback our managers are giving. Below are some examples of real feedback, and how we would rewrite it.

Before (ruinous empathy):

"I wish we had taken more time to test the widget feature better. It seems that a lot of the issues we had could have been prevented by better testing in dev; if we had a better environment in there, it would help as well. I'll talk to sysops about it and start to thinking on it. Would be great for us to build a culture of testing things better early on locally and in dev before moving to staging and production."

Notice the ruinous empathist uses the word “we,” rather than being direct. They also beat around the bush, not directly addressing the issue, and start making excuses for the report.

Let’s rewrite that with some radical candor:

"The widget feature had a number of bugs in it which caused two customer complaints. It looks like you didn’t write any tests for it. When you don’t take the time to test, I get scared because the story in my head is that you don’t care about testing which is going to cause more bugs, decrease our shipping speed, and ultimately could make this new product fail. Can you ensure that the work you’re doing in the future is well tested?"

Notice how direct that is. The manager speaks in inarguable truths and demonstrates some vulnerability.

Let’s take a look at another example. First, the ruinous empathy:

"I wish we had communicated better around the Facebook fix. It feels like you never got to prioritize it after our conversation. If we had discussed it earlier, maybe I could have that assigned to someone else. Nothing huge, but probably something we can learn from."

Notice the use of “we” again, and “feels like” to refer to something that isn’t a feeling. Also notice the weasel get-out excuse baked right in (presumably to make them feel better). Let’s try a rewrite:

"When you said you would prioritize fixing that bug with Facebook, and never created a prioritization card in Asana, I felt scared. The story in my head is that you don’t understand how important it is to the company we get this fixed, and you do not think it is important to keep to your commitments. Going forward, when you agree to something, can you do it?"