Delegation is the art of scaling yourself by distributing work across your team. The paradox of delegation is that it requires a degree of inefficiency and failure in the short term to work in the long term.

For example, let's say you have a task that needs doing. You look across your team, and decide that this work will only get done to your satisfaction if you're the one doing it. So you carve out some time to tackle it yourself.

At Clearbit, we call this heroing. Even if you're correct that you're the best person for the job, by not delegating, you're ensuring that your team never learns how to do this work, and subsequently your handling of this work can't be scaled.

For some work, this might make sense. For example, a CEO can't delegate a board meeting. However, you will find that most work can effectively be delegated. While initially it may not be done as well as you could have done it, the advantage of training your team and scaling yourself is worth it.

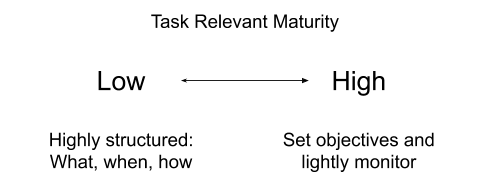

Task Relevant Maturity

So we've said before that great managers set goals, not tasks. However, what do you do in a case when someone has no experience in a particular area? Should you set a goal and leave them to sink or swim, or should you manage them closely by continuously asking for status reports and offering help? Task Relevant Maturity (TRM) answers this.

How often you monitor should not be based on what you believe your subordinate can do in general, but on his experience with a specific task and his prior performance with it – his task relevant maturity…as the subordinate’s work improves over time, you should respond with a corresponding reduction in the intensity of the monitoring.

- Andy Grove, High Output Management

So for reports that have no experience in an area (and therefore low TRM), then you need to be incredibly structured and closely manage their work. If they have done this task many times, then you can be far more laissez-faire and just check in occasionally. Managing this is a balance between micromanaging people's work and abdicating total responsibility.

As you can imagine, TRM is both very report- and task-specific. It is entirely possible for a person or a group of people to have a TRM that is high in one job but low in another. You want to raise a given person's TRM as fast as possible, to the point where you are setting mutually agreed-upon goals with occasional check-ins.

Delegating decision making

It's tempting to try and make all the decisions yourself. After all, you might have a lot of context and you might have been at the company longer than your team—surely you're going to make better decisions?

However, this gets into the management trap we discussed earlier. By not trusting your team, they will never learn to make decisions themselves, and you can never scale (or go on vacation).

By default you should be delegating decisions. Some decisions are too mundane for making the best use of your time (what coffee filters to buy), and some decisions are too specific and require domain knowledge you may not have. Know that anytime you make a decision (or override your team), you burn social capital with them; you're showing them you don't trust them.

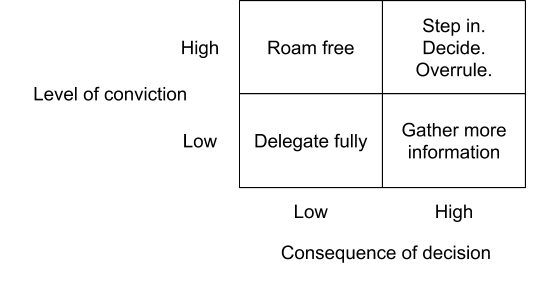

Trust requires judgment, which requires trial and error. Delegating decisions, therefore, inherently involves a degree of inefficiency and failure. In most cases a certain level of failure is acceptable, but what do you do in cases where failure is catastrophic? There is a simple framework.

The trade-off is between your level of conviction (i.e., do you think you know the ideal right answer?) and the consequence (i.e., if you make the wrong decision, how catastrophic is the downside?).

Here's how you should think about using the framework: when your conviction is low and the consequence low, delegate the project fully. When your conviction is high and the consequences low, delegate but monitor closely—it's better to extend the rope and let your report gain experience (and TRM). When the consequences are high, you either need to gather more data or overrule.

One way of understanding the consequence of a decision is determining whether that decision can be reversed or not. We call these Type 1 or Type 2 decisions, and we cover them in Decision making.