In the early days of Clearbit, if you wanted to know what anyone was working on, you could just lean right over and ask them. Even at 50-ish employees, we did all-hands updates from every department. Now, at 100 people, it’s now impossible for one person to know what everyone is working on. It’s just too much information.

We asked Kenny Van Zant, one of our angel investors, about how to improve internal communication. He said, “I think you mean planning. Communication and planning are interchangeable.” In other words, plan well and you will communicate well.

None of us need to know what every individual is working on. Knowing at least what every department’s priorities are, though, is a key part of having clarity. If people don’t have true clarity around what they're doing and how it fits into their organization, they’re bound to duplicate efforts, deflate morale, spend hours on unimportant tasks, and more.

There's an excellent article on this in The First Round Review. To quote the pertinent parts:

When people don’t know the order of operations, you get confusion, tension, drama. People get territorial because someone is already doing what they think they should be doing. And all you see are emails and meetings asking the same question over and over, ‘What are you working on this week?’

When the details of projects, including who is responsible for what, exists outside a manager’s head, and you make all this information available to everyone, you spread out accountability. It suddenly becomes very clear when someone has dropped the ball, or if someone doesn’t have time to take on more work, or if more steps need to be taken before launch. Everyone is responsible for seeing and understanding the situation.

When management is freed up, they can focus their energy on more important things: Developing their people, providing important context around projects, upgrading tools. They’re no longer spending all their time and energy simply serving as an information conduit. If your manager already knows what you’re working on and the status of your work, you can use that meeting time that would otherwise be about what you did that week to talk about how you want to develop in your role, how you want to participate in the future of the company, etc. This is how great companies grow their futures.

- Asana’s Justin Rosenstein on the One Quality Every Startup Needs to Survive

There are six questions that everyone should be able to answer for them to have clarity:

- What are you working on right now?

- Are you confident that it’s the most important thing you could be doing?

- Do you know who is waiting on you?

- Do you know who you can go to for support?

- Do you know how your work fits into the overarching product we’re trying to create?

- Do you know why that product matters?

Or to summarize, clarity is composed of clarity of purpose, clarity of the plan, and clarity of responsibility.

The Pyramid of Clarity

It's no surprise that Asana (the company) dogfoods their own products and, being in the space they're in, they know a thing or two about planning.

Internally they use something called The Pyramid of Clarity to ensure that everyone is aligned and working toward common goals. To quote them:

The Pyramid of Clarity shows how our longer-term aspirations are built on top of shorter-term goals, whether we’re building our product roadmap or business plans. We regularly refer back to the Pyramid of Clarity to help us stay on the same page, build confidence in our strategy and execution, and help individuals make decisions that are in line with the big picture.

The Pyramid of Clarity is a simple hierarchy of mission, strategies, objectives, and key-results. We prefer it over classical OKR systems because it's simpler (less hierarchy) and still manages to incorporate a larger mission.

This may seem like a lot of overhead, but you either pay the price of using this framework to consistently communicate (and how well you are performing) or you don’t, and you have to respond on the backend to people who don’t understand or get off track.

Mission

Great missions are short, clear, and could be stitched on a pillow. Things to remember about a good mission:

- Keep it high level. In general, a good mission tells someone who has never heard of your company not only what you do, but also why you started the business.

- A good litmus test is, if you tell your mission to a stranger, they can see why you're spending your life working on that.

- You want to tread the line between missions that are sufficiently broad and motivating, and those that are also specific enough. If you find yourself not referring to it a lot, it's not the right specificity.

Some good examples are:

- Asana: Enabling the world's teams to work together effortlessly

- Stripe: Increase the GDP of the internet

- Airbnb: Belong anywhere

- Google: Organize the world's information

- Nike: Bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world

Strategies

If the mission is the “why” (inarguable because it’s about passion), your strategies are “how” you will do it. At Asana, their strategy had three elements:

- Go build the best product in work management.

- Generate enough revenue to sustain the business and attract high quality stakeholders.

- Build the best team.

At Clearbit, we generally have four strategies for each year. In 2020 they were:

- Focus, focus, focus — on our ICP ( less than 100K Alexa B2B companies)

- Deliver measurable impact for our ICP customers by building the next generation of marketing tools

- Be a “self-growth vehicle” for everyone on our team

- Continuously improve the unit economics (for our ICP) to build a business capable of growth in times of boom and bust

Objectives

At the tactical level, objectives are the tactical goal posts along the way toward accomplishing the strategies and ultimately the mission.

Here are some examples of our objectives over the years:

- Create a predictable product development process

- Create a relationship with all of our target accounts (Engagement, MQLs, Predicted Pipeline)

- Strengthen our culture of regular, candid bidirectional feedback

- Sustain a highly collaborative, inclusive, and remote-friendly culture

Objectives map to the strategies (and drive them). If you have big objectives that don't map to your strategies, it's a sign that your strategies should be tweaked.

Unlike classical OKR systems, we have a flat list of objectives and key results that don't inherit from one another. We have found that cascading OKRs don’t work because it’s confusing and results in sub-OKRs getting hidden and forgotten about.

Objectives should be realistically achievable within the year. There may be a lot of objectives (we have 10 top-level objectives this year). It's important that every objective is something the company should be doing, and that everyone's work contributes to at least one of them.

Objectives generally aren’t quantifiable—that’s the role of key results (covered next). We sometimes break this rule by having big revenue numbers in our objectives, but usually key results are what we are measuring against, not objectives.

Objectives are owned by an executive. They don't need to be restricted to a specific business area; they can have cross-functional boundaries or be company wide (one of the reasons they need to be executive owned).

The key is to be clear and simple. The organization of objectives gives everyone a framework to refer to—and it’s also a communication framework, a roadmap to connect whatever you're working on all the way up to the mission.

If you find that parts of the organization are resisting negatively to the idea of objectives (or key results) in principle, rather than taking issue with a specific objective, that’s a red flag. It’s really important to identify those people early—many of them tap out because they don’t like scrutiny on their prioritization or work.

Once your objectives are laid out, have multiple teams write key results against them.

Key results

Key results are measurements against your objectives to show how you're performing against them; for example, “generate $20M in new ARR.” Every team will write key results against the various company objectives. They are refreshed quarterly.

Key results are:

- Clearly defined

- Owned by a single person (usually a team lead)

- Objective, in that a third party should be able to confirm their current status

- Ideally an integer value (rather than a true/false Boolean that has no concept of progress over time)

Whoever owns the key result should either have total control over the outcome (i.e., successfully achieving the key result doesn't hinge on teams that aren't reporting to them) or be an executive.

It’s important that the team feels autonomy and agency over moving the key result. They shouldn’t have to rely on other teams not under their control to achieve success.

That said, cross-functional objectives are often necessary. This is why we require cross-functional objectives to be owned by an executive who is often able to exert more influence over the organization and is more prepared to take ownership of things outside of their control.

One of the lessons we learned here is how to phrase KRs so others get a sense of progress. We use this format: From X to Y in metric. For example:

- From $10M to $20M in ARR

- From 10s to less than 1s in page load time

- From unknown to 40% 30d retention

Or written differently to achieve the same effect:

- generate $20M ARR (up from $10M in q2)

We do it so that it communicates clearly how much velocity will be required to meet that goal and also whether there's a baseline available for it or not.

We suggest creating a Mode dashboard for each objective, listing out all the key results and their current value.

Initiatives

Lastly, initiatives are small projects that aim to drive progress against key results. They are small units of work at the single individual contributor level. They should be completely under the control of whoever owns them.

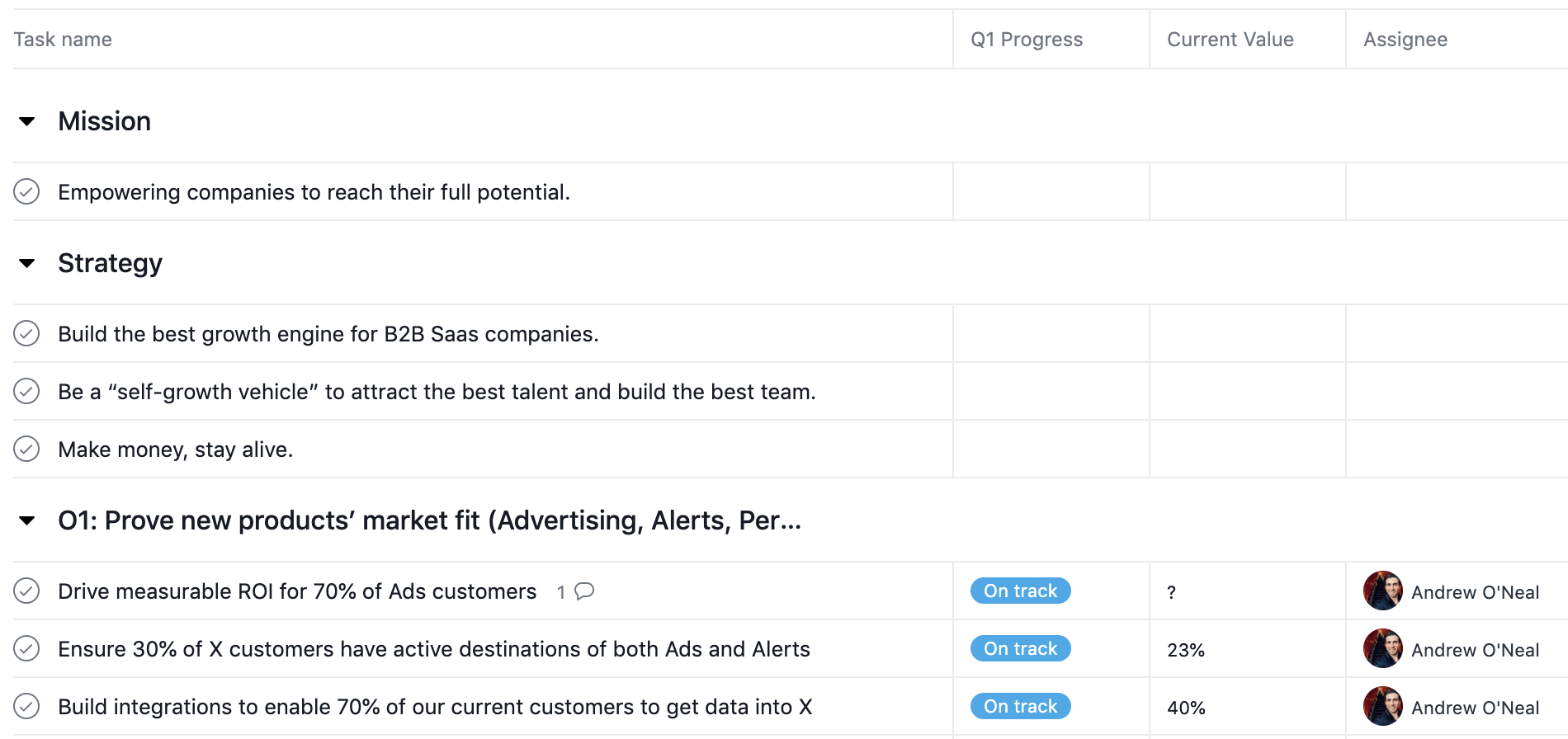

Recording OKRs

Our Pyramid of Clarity is stored in Asana. We use tasks for each objective. Key results are nestled under each objective as subtasks.

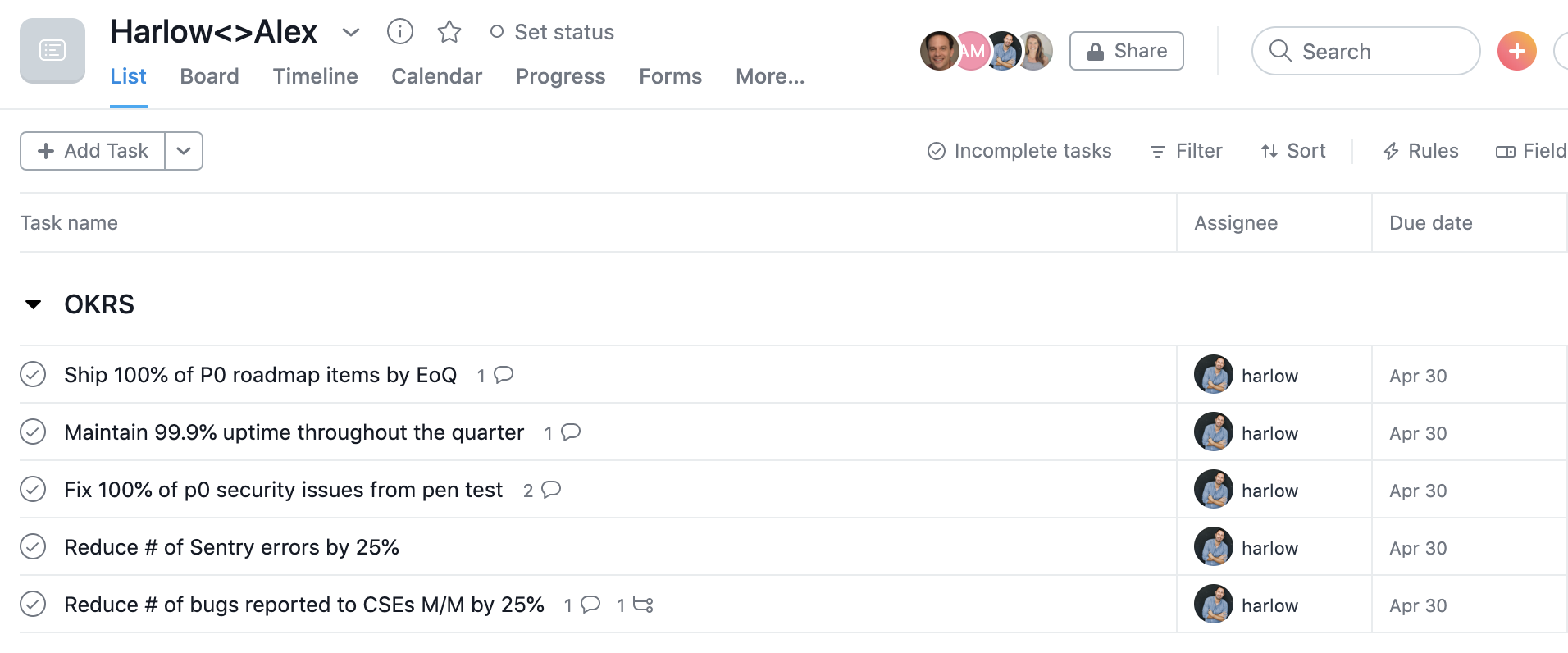

Updating key results

Every key result is also copied over to the owner's one-on-one board using Asana’s Add this task to another project feature. There they can be updated prior to the one-on-one and referenced throughout the meeting.

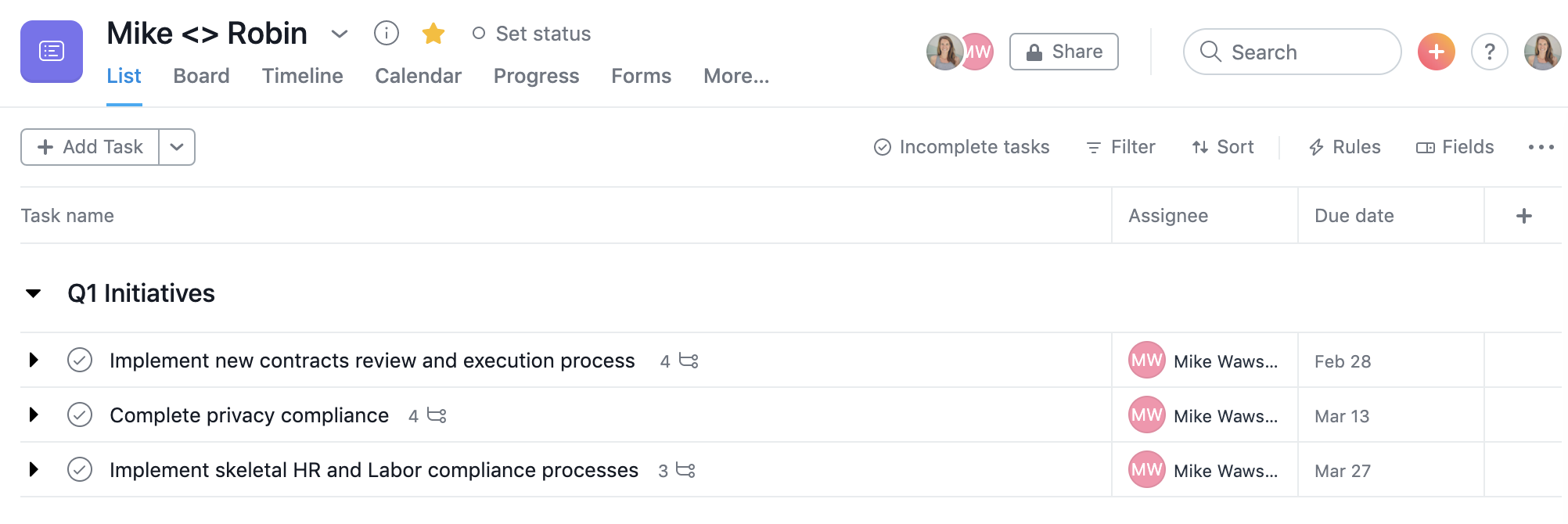

Updating Initiatives

For ICs that don't directly own a key result, their initiatives driving work toward the key result should be at the top of their one-on-one project.

Example of Q1 Initiatives at top of 1:1 board